All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Arvel MAG

“Stand-to! Stand-to!” roared the inebriated and corpulentsergeant as he stumbled into the dugout. Dark and filthy, it was a treacherous place to be drunk.What that man could smuggle into the trenches was utterly amazing: scotch, whiskey, brandy,Army-issued rum, and, of course, the best French wines were seldom in short supply (naturally, allfor a price). Unfortunately, for once he had decided to follow orders.

Slowly, lazily, themen were torn from comforting dreams of home, their sweethearts, and clean beds and thrown backinto reality. They sat up blinking and rubbing their eyes like little boys at a summer campuntil the sergeant prodded them with a shovel, after which they began moving in earnest. Sleep andthe few minutes before it were the only parts of a soldier’s day that he really owned; therest were property of the Royal Army.

Arvel watched as the men got up; he liked watchingothers, he had been a painter before the war. He even fancied himself a bit of a philosopher.Observing others made him feel secure, somehow included in humanity yet satisfactorily alone. Heknew he was just one ant in a vast ant farm, a part of a whole, but he held onto that part withinexhaustible resolve.

Now the men donned their great coats and helmets and gave theirrifles a look-over, and Arvel did this too. There were the tired, vapid veterans of trench warfare;each of their motions was carried out smoothly and with the quiet precision that only comes withcountless repetition. Green recruits were constantly filled with anxiety and apprehension, duckingand dashing every shell. The trenches were such a hell for these people that their fear of theplethora of ways a man could unexpectedly die either paralyzed them, gave them shell-shock orturned them into near-callous animals, as happened to most.

Together they ambled out of thedugout for the morning ritual: the stand-to. Quickly, silently, the word was to be spread down theline, and everyone in the trenches was to stand on the fire-step with fixed bayonets for an houruntil the light was considered too good for an enemy offensive. Past experience had shown that themost likely times for a Boche attack were dawn and dusk, when the light was sufficient to see butnot enough for the defenders to have a good shot.

However, an hour of standing on a ledge istedious even for a painter, so Arvel’s mind wandered like Cain in the land of Nod. If he everwanted to paint his war memories, as he was sure he would, the thought occurred to him that hispaint selection would be very limited; his and everyone else’s uniforms were a muddyolive-green, and everything else was either mud or mud-coated. It was the most drab, slimy, andoverall inhospitable landscape he could ever put on canvas.

In front of him was barbedwire. It was not an orderly system of posts and coils or rows but a tall, haphazardlyconstructed labyrinth, an imposing and menacing tangle of little knives sometimes six feet thick inboth directions. God help the man who had to go through that. God help me, Arvel thought.

Beyond the wire was no man’s land. It was once probably some farmer’s grazing field forlivestock, but now it was transformed by the might of man and machines into shell hole after shellhole. Sometimes there was a body in view to make things interesting or provide marksmanshippractice, but other than that, there was hardly a square inch of undisturbed earth. Arvel knew thiswasn’t bad though; it was what kept him alive.

Mother Earth, however contorted, wasalways there for her soldier, protecting him from shells and keeping him out of the sight of theenemy. Arvel couldn’t remember how many times he had thought while advancing, Maybe if I holdher real tight, if I throw myself down on top of her, she’ll save me, she’ll hide mefrom the shells and the men who want to kill me. Oh God, oh God, why do they want to kill me? Iwant to live, please, save me.

Beyond that was the enemy’s barbed wire and theirtrenches, exactly like their British counterparts. There were hardly any differences; everythingwas so reciprocal. Arvel couldn’t even remember why he signed up for a war that didn’tconcern him, a war where he attacked, counter-attacked, defended, waited, and so on ad infinitum.Wait, yes, he remembered: he signed up because all his friends were going, and it was a jolly goodthing to do, right? Too bad they were all either dead or hospitalized, lucky ba----ds.

Thenthe stand-down order released the men to clean their rifles and do what they wanted untilbreakfast, maybe even have a tot of rum. Arvel was not reluctant to descend into the dugout, as theJanuary wind blew a nauseating odor. Moving the dead was a major logistical problem in thetrenches. In the heat of battle, one can’t be expected to somehow heave friends’ bodiesbehind the lines without being shot, so some were simply buried under the trenches. (As if toemphasize the point, Arvel stumbled over the jaw of a Frenchman jutting from the ground.) However,what more commonly happened was that bodies near the wire in no man’s land would be left forweeks or months. After one especially ferocious battle, a young German ended up dead on the wire,but in such a way that he was propped up in an eerily upright position so it looked as if he weresuspended in mid-stride, arms raised in supplication. The little bugger was quite fun to shoot. Oneday, Arvel’s captain was inspecting the trenches and was mortified by the putrid odor of thiscorpse, so a detachment (including Arvel) was sent out to give it a proper burial. It wasn’teasy; in the process, the German’s arms detached from his body. He had to be buried on thespot.

The very next day, a shell landed precisely on his grave, sending the body and itsremaining limbs flailing back onto the wire. Arvel pronounced it fate, and the battalion once againhad a target.

But all this morbid reflection was about to spoil his breakfast, so Arveltrudged back to his hole. To his great dismay, the odor had penetrated his dugout, rendering eatingdifficult. Arvel’s diet consisted mainly of canned corned beef, bread (made mostly of driedand ground turnips, due to a flour shortage), and biscuits. On occasion there was thin pea soupwith horsemeat, but that was attained only by chance or through the sergeant’s skill.

“The sustenance is barely sustainable,” Arvel remarked quietly to himself,whose voice from long silences was hoarse. Who said that, he wondered. Whoever it was, he must haveonce liked the author a lot, or else he wouldn’t have remembered it.

Arvel hadconcluded long ago that there was little point in having friends in the trenches; either God or theKaiser wouldn’t let you keep them. His last attempt at a friend was little Stephen, barely 18and a runt at that. Stephen was ever the optimist and a comic, seeing the best in every situationand making fun of it. Arvel came to depend on his wit like a crutch, as it was the only way hecould find to keep himself mentally alive.

One night, Stephen dreamt that his old tabby cat,Mr. Fruitcake, was gently purring on his legs. To his horror, he awoke to find that two enormousrats were fighting over the remains of a hand in his bed. After that, he was quieter and preferredto spend his nights in a corner with a lighted candle and a bayonet to hunt the rodents. One paircould produce 880 offspring in a single year, so he had quite a task. Stephen had a bad habit ofgrowing sleepy after a few successful lunges and often fell asleep. Once he let a rat go by and itbegan to drag off his candle, leaving him in the darkness.

Arvel would find him later in noman’s land near the Germans with no less than 12 Mauser bullets in his chest and anexpression of extreme hysteria on his face.

That was why Arvel kept to himself these days.He found that it kept him focused, self-reliant, emotionally protected, and most importantly,alive. Stephen’s case was rare, and most of Arvel’s day was spent staring at the sky(vertical height was limited by sniper’s bullets) or at the trench walls to see if theyneeded maintenance.

The Germans had picked up the pace of their shelling today, he noted.The shelling by both sides ran an unceasing 24 hours a day, with a dramatic increase commonlyinterpreted as a sign of a coming attack.

Arvel was replacing sandbags when he heard ahigh-pitched whistle heading in his direction. He dove into the nearest hole, barely escaping theearth-shattering high explosive shell, which transformed his dugout into a grave for those inside.Arvel praised God for saving what little was left of his life. Chains of whistles could be heardand the German army rose as one from the ground. The attack had begun, strategically catching themen when they were lowest on reserves. That old hate again filled the friendless void of his chest.They were coming with grotesque gas masks - those murderous ba----ds, they were going to gas theentire line. Arvel’s own gas hood was in the dugout, leaving him vulnerable.

They wereat the wire; the machine gunners hadn’t time to man their weapons and shoot them down.Don’t ever think during an attack. Never. Arvel whipped out his Lee-Enfield

rifle andwas jamming rounds into the magazine when the German drove a bayonet into his rib cage. Arvelslumped back into the bloodstained trench wall, clutching the excruciatingly painful hole in hischest, trying to hold back his blood, his memories, his very existence. He couldn’t stophimself from diffusing into nothingness. Why, why, why didn’t he have control anymore? Then,his face, his arms, and his entire body gave one convulsing shiver before relaxing willfully intohis mother’s arms as she softly sang a sweet Welsh lullaby.

Hunan blensyn, ar fymynwes

Clyd a chynnes ydyiv hon

Breichiau mam sy ’n dyn amdanat

Cariadmam sy danfy mron

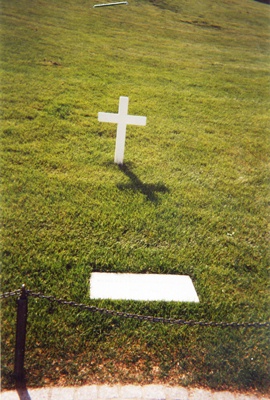

The snow that gently fell around him formed his only grave; it was as ifthe mother who was always there for her soldier didn’t forget to tuck him in with a whiteblanket outlined by his blood.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 6 comments.

0 articles 0 photos 12292 comments