All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Chasing Cars

I remember. The doctors tell me I was knocked out and any way of me being conscious was completely arbitrary. But I knew I was awake. At least, for some of it. I could envision the dark smoke, deepening in color as it reached its source of life, dissolving within touch. The shimmering embers dissolving above the now-doused fire, burning into my memory. The doctors were wrong. I could still smell the scorching rubber and leaking gas, even after four months. It had embedded into my mind so deep that no amount of psychiatric sessions could loosen it.

The worst part about remembering was the sound. The tires rubbing fiercely against the pavement, pleading for traction. The windows shattered so loud you didn’t even have to open your eyes to know that the glass now stained your face with blood. Hell, I could still taste the blood. I still have yet to convince myself that I was, in fact, my own. The blood tasted bitter and warm as I felt it seep from my bitten tongue and trickle down my sliced chin. Even then, the one thing forever engraved into my pain-induced soul, was seeing my father lying on the hood of our car.

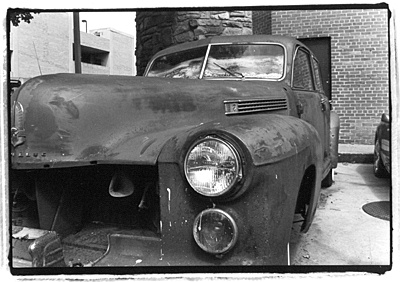

It had been a long day at school, and it was one of those times when the clock seemed to tick slower than it tocked. I was more than happy to be going home for the weekend, planning on sleeping away the majority of it. I recall sitting in my history class, glancing out the window over Kathy Banks and watching a fresh layer of snow stick to the ground. I thought nothing of it. It was light and pretty, and I wasn’t driving. As the last bell rang the sign of freedom, I grabbed my things and headed to my locker. I twisted the combination, threw my books into my torn backpack, and slammed the locker shut. I walked out the side door towards the 1989 Honda Civic my dad was maneuvering.

To understand my father, you need to recognize his passions: cigarettes, drugs, and alcohol. He’s described to me on more than one occasion how the alcohol climbs down your throat and tingles your belly, and it just makes you feel okay with the fact that you got fired from work that day, or the girl you’ve been trying to ask out turned you down flat. Alcohol, as he defined, was like punching a bastard in the face. Except you wouldn’t get arrested for assault. My father became a heavy drinker about eight years ago, when he learned my mother was cheating on him; now he used the alcohol to “numb the pain.”

I hopped into the front seat to my father wearing a stained gray sweatshirt with faded blue jeans. I could smell the Jack Daniels from the passenger’s side; I could already tell that he had more than three bottles. I also knew that this meant my mother had called – from my stepdad’s house phone – discussing court dates for child custody. I always reassured my dad by calling her a heartless b****, but I loved her still.

“How’s school,” he asked, more as a demand than a question.

“Okay. Want me to drive?”

Even though I was only fourteen, I had driven my father’s car hundreds of times, and it became habitual for me to take the wheel while he was “indisposed.” In my opinion, the roads would be safer if a sober fourteen year old boy took over for a hammered thirty-five year old man. I reached for the steering wheel as he clutched his hand around my wrist. His palms were rough and cold to the touch, and I noticed he had fresh cuts on the finger where his wedding ring once belonged.

“No, Andy. I’m drivin’,” he stammered. He relaxed his grip as I released mine, and we veered out of the parking lot. I didn’t noticed until I saw the police reports, but my father never put on his seatbelt.

I had driven with my father when he was drunk more than he was sober. He wasn’t a great driver, but he wasn’t terrible. I mean, he made one mistake in my fourteen years. One wrong turn.

As he pulled to the stop sign a few miles from the highway, he turned on the CD player to blast Santana, his favorite band. This led into him telling me the story of where he was born at Woodstock, specifically during the Santana set. We both knew it was a lie since he was born in the seventies, but it made him feel a connection with something other than the bottle in his fist.

I reclined the seat back and closed my eyes, only to be jolted forward a few seconds later. I lifted my head to discover my father crying. Not sad tears. Angry tears. The kind that makes you want to yell at your dog. Or, in my father’s condition, turn left onto the busiest intersection in the state.

Doctors ask me what angry tears meant. Why was he crying? Was he really crying, they’d say, peering at me through their glasses with their beady eyes, prodding me like a bug underneath a microscope. And that’s when I’d scream and knock over their potted plant and dared them to ask me one more time if he was actually crying. You never forget the first time you see your father cry. All I know is that was the last mental image I have of my father.

The accident, I swear, happened in slow motion. My father forcing the wheel left and smashing the gas pedal to the floor, barreling us down the interstate on the wrong side of the road. Watching the speedometer steadily climb: 68, 69, 70 miles per hour. Watching the snow hit against our window like bullets from a gun. And then, the soft flicker of the oncoming car’s headlight hurdling towards us. And then, nothing.

This is the part the doctors had correct. I was knocked out cold on impact. I didn’t see our car collide with the 1992 Ford truck, pulverizing the entire front of our Civic. I wasn’t awake to witness my father flying through the windshield and slicing open his neck. I was unconscious when the splintered glass hit my face like acid and cut open my cheek and left a gash on my mouth. I couldn’t feel my teeth bite down against my tongue, almost tearing it completely in two. I started to regain consciousness when the airbag pushed against my face, breaking my neck and leaving me with only 76% movement in my spinal cord. It was that moment when I saw my father laying between the two cars with his neck completely split open and his body mangled so badly he looked as if he was mauled by the devil himself.

My brain started to go in and out at this point, but I caught fuzzy glimpses of what was happening around me. I remember them taking care of the guy in the other car, who broke several ribs and had a severe cut on his head. Still, I remember sitting there, strapped to my seat, wanting to scream at the damn paramedics to go take of my father who was probably dead by then. But I couldn’t. My voice was stuck in my throat and nothing came out except desperate gasps for air. Finally a paramedic reached my father and loaded him into the ambulance and furiously hooked him up to a machine. I blacked out again when I saw them use these two metal pads and thrust them against my father’s wounded chest, striking electricity into his system.

I woke up five days later in a hospital that smelled like saline and rubber gloves. I had an IV of fresh oxygen injected into the vein on my left arm, and I could feel gauze wrapped around my head. I was in stable condition, with a neck brace for the next couple of weeks. I felt like I was in a trance: the entire room was brightly lit, and the colors of the walls were so pale I felt as if I was trapped within myself. The room seemed so small and so tight, that it was a struggle to breathe. I began to shift uncomfortably in the hospital bed, only to be startled by my mother. The mother whom I hadn’t seen since Christmas – three years ago.

“Shh, honey, it’s okay, you’re okay,” she whispered as tears streamed down her cheek. And as I saw the tears stain her face, I remembered everything that had happened. The car. The snow. The wreck. My father.

“Dad,” I croaked, struggling to find my voice.

She hesitated. I watched as her green eyes dulled from the excitement. I also knew when she bit her lip and looked down that something was very wrong.

“Your father didn’t make it, sweetie.”

This was the point where the doctors would ask me how I felt about this happening. What kind of question is that? How would you feel if your father was killed in a car accident, when he was the drunk driver? When your father is considered the villain in the story? You sure as hell wouldn’t want some doctor trying to relate to you when he has a picture of both of his healthy and living parents framed on his desk. I would scream to them that it sucked, and I would walk out of the room. The funny thing was that the therapy sessions did more damage to me than any accident could have ever done.

“Your father died in the ambulance five days ago, Andy. The doctors say he felt nothing. You’re probably very tired, you’ve been in a coma for the past couple of days,” she continued on, now gripping my hand. I felt her wipe away the tears streaking down my cheeks, but I pushed her away. I wiped the tears away myself and forced myself to stop crying. The last thing I ever saw my father do emotionally was cry, and that was the last thing I wanted to do.

So four days later there I was, sitting in a musty funeral home surrounding by sobbing relatives. Weeping over my father’s closed casket, or crying over me, sitting unpleasantly in the rented wheelchair I still use today. I reassured them I was recovering well, but they refused to stop apologizing. Like them saying they were sorry for my accident would bring back my father and stop him from chugging alcohol before he picked me up from school. Like the apologizing would make this nightmare end and I would wake up in my bed and laugh at the dream. But it wasn’t a dream. And I didn’t want their pity, I wanted my father. I wanted the man who taught me how to play checkers and shoot a basketball. The man who was drunk the majority of my childhood, but never once laid a hand on me until the day of the accident. And he was there. Except, now he was wearing a wrinkled black suit that he only wore to job interviews, and could never smile back to me.

I sat there in the front of the church, barely listening to the Gospel the preacher gave. I had no idea how he would tie this in with my father being dead. All I wanted was to get out of that church. I didn’t know where I would go, but I just needed to leave. But no matter where I went, I couldn’t escape it. It follows you like the moon follows you when you drive. There’s no getting rid of it. But even the moon comes back after the sun is done with the day. The only difference was my father wasn’t going to come back to life after sunset.

It was lightly raining when they lowered my father’s body into the muddy ground. It was fitting, because he loved the rain. “Isn’t it just so calming?” he would say, as he took a swig of Captain Morgan. “Nothing more relaxing than a lazy Sunday with a couple of drinks and your best bud,” he’d say, wrapping me in with a big bear hug. He smelled like wood and alcohol. I know it sounds like a terrible combination, but it became the association with my father, and a part of his charm. It was the smell that swallowed our house, the one stuck in our couch cushions. As the preacher gave one final prayer before we left my father alone in the dirt forever, I was handed a rose. The rose wasn’t red, but it wasn’t pink. It was that strange in between where the flower couldn’t decide what color it wanted to be, so it just chose both. I watched my family throw the roses into the hole that now held my father, and when it came to my turn, I hesitated. Oh God, why did I hesitate?

“Are you okay, Andy?” said Dr. Hardwick. “Do you need a tissue?”

“No,” I sniffed, wiping away tears. “I’m fine. It’s just, I….Why did I hesitate?”

I felt Dr. Hardwick put his hand on my arm. His palms were rough and cold to the touch, and I saw he had some old scars on his finger where his wedding ring was.

“Maybe you hesitated because you didn’t want to lose your father?” he suggested, trying to reassure me. After months of hearing doctors talk at me, Dr. Hardwick was the first one I let dive into my emotions. He was the first person I let see me cry since that day, four months ago. There was something about him that made me feel at ease. I took a deep breath, and began to describe the rest of the day after I finally threw the rose in with the rest of them. Yet, all I could focus on was the stain on Dr. Hardwick’s gray shirt. Or the framed Santana poster, hanging above his desk. I finished my story, and I accepted the tissues he held out for me. I sat there in my wheelchair and listened to Dr. Hardwick give his input on the situation. I watched him fiddle with a loose string on the navy blue couch he was sitting upright on. Our Civic was navy blue.

I remember. The doctors tell me I was knocked out and any way of me being conscious was completely arbitrary. But I knew I was awake. At least, for some of it. I could envision the dark smoke, deepening in color as it reached its source of life, dissolving within touch. The shimmering embers dissolving above the now-doused fire, burning into my memory. The doctors were wrong. I could still smell the scorching rubber and leaking gas, even after four months. It had embedded into my mind so deep that no amount of psychiatric sessions could loosen it.

The worst part about remembering was the sound. The tires rubbing fiercely against the pavement, pleading for traction. The windows shattered so loud you didn’t even have to open your eyes to know that the glass now stained your face with blood. Hell, I could still taste the blood. I still have yet to convince myself that I was, in fact, my own. The blood tasted bitter and warm as I felt it seep from my bitten tongue and trickle down my sliced chin. Even then, the one thing forever engraved into my pain-induced soul, was seeing my father lying on the hood of our car.

It had been a long day at school, and it was one of those times when the clock seemed to tick slower than it tocked. I was more than happy to be going home for the weekend, planning on sleeping away the majority of it. I recall sitting in my history class, glancing out the window over Kathy Banks and watching a fresh layer of snow stick to the ground. I thought nothing of it. It was light and pretty, and I wasn’t driving. As the last bell rang the sign of freedom, I grabbed my things and headed to my locker. I twisted the combination, threw my books into my torn backpack, and slammed the locker shut. I walked out the side door towards the 1989 Honda Civic my dad was maneuvering.

To understand my father, you need to recognize his passions: cigarettes, drugs, and alcohol. He’s described to me on more than one occasion how the alcohol climbs down your throat and tingles your belly, and it just makes you feel okay with the fact that you got fired from work that day, or the girl you’ve been trying to ask out turned you down flat. Alcohol, as he defined, was like punching a bastard in the face. Except you wouldn’t get arrested for assault. My father became a heavy drinker about eight years ago, when he learned my mother was cheating on him; now he used the alcohol to “numb the pain.”

I hopped into the front seat to my father wearing a stained gray sweatshirt with faded blue jeans. I could smell the Jack Daniels from the passenger’s side; I could already tell that he had more than three bottles. I also knew that this meant my mother had called – from my stepdad’s house phone – discussing court dates for child custody. I always reassured my dad by calling her a heartless b****, but I loved her still.

“How’s school,” he asked, more as a demand than a question.

“Okay. Want me to drive?”

Even though I was only fourteen, I had driven my father’s car hundreds of times, and it became habitual for me to take the wheel while he was “indisposed.” In my opinion, the roads would be safer if a sober fourteen year old boy took over for a hammered thirty-five year old man. I reached for the steering wheel as he clutched his hand around my wrist. His palms were rough and cold to the touch, and I noticed he had fresh cuts on the finger where his wedding ring once belonged.

“No, Andy. I’m drivin’,” he stammered. He relaxed his grip as I released mine, and we veered out of the parking lot. I didn’t noticed until I saw the police reports, but my father never put on his seatbelt.

I had driven with my father when he was drunk more than he was sober. He wasn’t a great driver, but he wasn’t terrible. I mean, he made one mistake in my fourteen years. One wrong turn.

As he pulled to the stop sign a few miles from the highway, he turned on the CD player to blast Santana, his favorite band. This led into him telling me the story of where he was born at Woodstock, specifically during the Santana set. We both knew it was a lie since he was born in the seventies, but it made him feel a connection with something other than the bottle in his fist.

I reclined the seat back and closed my eyes, only to be jolted forward a few seconds later. I lifted my head to discover my father crying. Not sad tears. Angry tears. The kind that makes you want to yell at your dog. Or, in my father’s condition, turn left onto the busiest intersection in the state.

Doctors ask me what angry tears meant. Why was he crying? Was he really crying, they’d say, peering at me through their glasses with their beady eyes, prodding me like a bug underneath a microscope. And that’s when I’d scream and knock over their potted plant and dared them to ask me one more time if he was actually crying. You never forget the first time you see your father cry. All I know is that was the last mental image I have of my father.

The accident, I swear, happened in slow motion. My father forcing the wheel left and smashing the gas pedal to the floor, barreling us down the interstate on the wrong side of the road. Watching the speedometer steadily climb: 68, 69, 70 miles per hour. Watching the snow hit against our window like bullets from a gun. And then, the soft flicker of the oncoming car’s headlight hurdling towards us. And then, nothing.

This is the part the doctors had correct. I was knocked out cold on impact. I didn’t see our car collide with the 1992 Ford truck, pulverizing the entire front of our Civic. I wasn’t awake to witness my father flying through the windshield and slicing open his neck. I was unconscious when the splintered glass hit my face like acid and cut open my cheek and left a gash on my mouth. I couldn’t feel my teeth bite down against my tongue, almost tearing it completely in two. I started to regain consciousness when the airbag pushed against my face, breaking my neck and leaving me with only 76% movement in my spinal cord. It was that moment when I saw my father laying between the two cars with his neck completely split open and his body mangled so badly he looked as if he was mauled by the devil himself.

My brain started to go in and out at this point, but I caught fuzzy glimpses of what was happening around me. I remember them taking care of the guy in the other car, who broke several ribs and had a severe cut on his head. Still, I remember sitting there, strapped to my seat, wanting to scream at the damn paramedics to go take of my father who was probably dead by then. But I couldn’t. My voice was stuck in my throat and nothing came out except desperate gasps for air. Finally a paramedic reached my father and loaded him into the ambulance and furiously hooked him up to a machine. I blacked out again when I saw them use these two metal pads and thrust them against my father’s wounded chest, striking electricity into his system.

I woke up five days later in a hospital that smelled like saline and rubber gloves. I had an IV of fresh oxygen injected into the vein on my left arm, and I could feel gauze wrapped around my head. I was in stable condition, with a neck brace for the next couple of weeks. I felt like I was in a trance: the entire room was brightly lit, and the colors of the walls were so pale I felt as if I was trapped within myself. The room seemed so small and so tight, that it was a struggle to breathe. I began to shift uncomfortably in the hospital bed, only to be startled by my mother. The mother whom I hadn’t seen since Christmas – three years ago.

“Shh, honey, it’s okay, you’re okay,” she whispered as tears streamed down her cheek. And as I saw the tears stain her face, I remembered everything that had happened. The car. The snow. The wreck. My father.

“Dad,” I croaked, struggling to find my voice.

She hesitated. I watched as her green eyes dulled from the excitement. I also knew when she bit her lip and looked down that something was very wrong.

“Your father didn’t make it, sweetie.”

This was the point where the doctors would ask me how I felt about this happening. What kind of question is that? How would you feel if your father was killed in a car accident, when he was the drunk driver? When your father is considered the villain in the story? You sure as hell wouldn’t want some doctor trying to relate to you when he has a picture of both of his healthy and living parents framed on his desk. I would scream to them that it sucked, and I would walk out of the room. The funny thing was that the therapy sessions did more damage to me than any accident could have ever done.

“Your father died in the ambulance five days ago, Andy. The doctors say he felt nothing. You’re probably very tired, you’ve been in a coma for the past couple of days,” she continued on, now gripping my hand. I felt her wipe away the tears streaking down my cheeks, but I pushed her away. I wiped the tears away myself and forced myself to stop crying. The last thing I ever saw my father do emotionally was cry, and that was the last thing I wanted to do.

So four days later there I was, sitting in a musty funeral home surrounding by sobbing relatives. Weeping over my father’s closed casket, or crying over me, sitting unpleasantly in the rented wheelchair I still use today. I reassured them I was recovering well, but they refused to stop apologizing. Like them saying they were sorry for my accident would bring back my father and stop him from chugging alcohol before he picked me up from school. Like the apologizing would make this nightmare end and I would wake up in my bed and laugh at the dream. But it wasn’t a dream. And I didn’t want their pity, I wanted my father. I wanted the man who taught me how to play checkers and shoot a basketball. The man who was drunk the majority of my childhood, but never once laid a hand on me until the day of the accident. And he was there. Except, now he was wearing a wrinkled black suit that he only wore to job interviews, and could never smile back to me.

I sat there in the front of the church, barely listening to the Gospel the preacher gave. I had no idea how he would tie this in with my father being dead. All I wanted was to get out of that church. I didn’t know where I would go, but I just needed to leave. But no matter where I went, I couldn’t escape it. It follows you like the moon follows you when you drive. There’s no getting rid of it. But even the moon comes back after the sun is done with the day. The only difference was my father wasn’t going to come back to life after sunset.

It was lightly raining when they lowered my father’s body into the muddy ground. It was fitting, because he loved the rain. “Isn’t it just so calming?” he would say, as he took a swig of Captain Morgan. “Nothing more relaxing than a lazy Sunday with a couple of drinks and your best bud,” he’d say, wrapping me in with a big bear hug. He smelled like wood and alcohol. I know it sounds like a terrible combination, but it became the association with my father, and a part of his charm. It was the smell that swallowed our house, the one stuck in our couch cushions. As the preacher gave one final prayer before we left my father alone in the dirt forever, I was handed a rose. The rose wasn’t red, but it wasn’t pink. It was that strange in between where the flower couldn’t decide what color it wanted to be, so it just chose both. I watched my family throw the roses into the hole that now held my father, and when it came to my turn, I hesitated. Oh God, why did I hesitate?

“Are you okay, Andy?” said Dr. Hardwick. “Do you need a tissue?”

“No,” I sniffed, wiping away tears. “I’m fine. It’s just, I….Why did I hesitate?”

I felt Dr. Hardwick put his hand on my arm. His palms were rough and cold to the touch, and I saw he had some old scars on his finger where his wedding ring was.

“Maybe you hesitated because you didn’t want to lose your father?” he suggested, trying to reassure me. After months of hearing doctors talk at me, Dr. Hardwick was the first one I let dive into my emotions. He was the first person I let see me cry since that day, four months ago. There was something about him that made me feel at ease. I took a deep breath, and began to describe the rest of the day after I finally threw the rose in with the rest of them. Yet, all I could focus on was the stain on Dr. Hardwick’s gray shirt. Or the framed Santana poster, hanging above his desk. I finished my story, and I accepted the tissues he held out for me. I sat there in my wheelchair and listened to Dr. Hardwick give his input on the situation. I watched him fiddle with a loose string on the navy blue couch he was sitting upright on. Our Civic was navy blue.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.