All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Metal and Sand

Li Hua had never been fond of the desert, something which she always felt the most after walking in it for several hours. She’d been searching for days, following the tattered map she’d been given, looking for the area where the rock had fallen. It had not of course had the courtesy to fall in one of the cities nearby or near the trading posts along the coast. Instead, almost as if it wished to irk her, it had landed in the middle of the desert. She didn’t even know what the rock was for, only that they needed her to find it and it shouldn’t be hard.

She’d left the city at dawn, nearly five hours ago for the last leg of her journey. Her camel had been stolen so she carried only what she needed: a canteen in a small knapsack along with food, the map, and the small tracking device to ensure that, if she were to get lost, she would be found again. Li Hua had come to two conclusions; either they didn’t trust her, or this task was more important or dangerous than she had been led to believe. She wasn’t sure which she preferred.

When she’d set off that morning, the thin fabric of her robe had gleamed white but the powerful winds had caught sand in the thread and turned it a strange, pale beige. She had the white veil which cascaded from her hat drawn up around her face; the headwear, which could be reversed to toss the white silk down the back of the head, were all the fashion back in the cities. Li Hua was fond of them for two reasons; they kept the sand out of her face and they helped her blend in. Out in the desert, the merchants were suspicious of foreigners, even more than the city folk were. It certainly didn’t help that her people owned nearly every grain of sand she tread on, every brick in the city streets.

Her sleeves were long to conceal the small device strapped to her palm. Every once in a while, Li Hua would pull back the fabric to see which way the tiny red arrow was pointing. It was, they had explained to her, attracted to the unique metals in the rock, and sensitive enough to register it nearly fifty miles away. She had been following it nearly exclusively since it had begun to vibrate the day before.

“This must be a very special rock,” she had said. They only nodded.

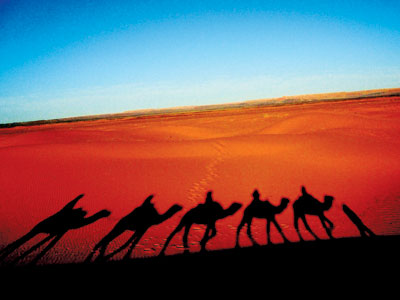

Li Hua looked in the direction of the arrow. In the distance, little more than a speck on the horizon, was a shape. A caravan. And the arrow was brightening, signifying that she was closer to her target. She hurried, eager for the journey to end.

Nearly an hour later she reached her destination. It was not a caravan; far too small. It was a small stand surrounded by canvas chairs. Behind the stand sat a native man in a tall turban and loose fitting white clothes like hers. He smiled at her and beckoned her over.

“Good day,” she greeted him with a slight bow. “Has anything…” she trailed off, her eyes caught by the one thing on the stand, a silver, multifaceted rock. She picked it up, running her fingers over the porous surface. The dial on her palm vibrated like an irritable insect. She held the rock up for the man to see. “Forgive me if this seems a strange question but did this fall from the sky?”

He smiled at her again, like a snake. His teeth were very white and very straight; his eyes blinked in a rhythm and did not match his grin. “It did. I take it you are here to fetch it. They told me you were on your way. Please sit down and let me explain.”

Li Hua put down the rock and pulled up one of the canvas chairs, unclasping her veil as she did so and watching the man carefully for any sign of hostility upon seeing her face. There was both a gun and a dagger hidden beneath her skirt.

The man showed no response, simply blinked at her once more. “They left me here to guard it.”

“Who is they?”

“My friends. Tell me,” he picked up the rock and tossed it back and forth in his hands. “What do you want with it?”

“I was sent here,” Li Hua shrugged, hating that she had to reveal her ignorance.

“I see,” he said in the manner of one who didn’t but had become bored with the strain of conversation. “How about this; I’ll make you a deal. I am not too fond of my friends right now; they left me after all. And I am very bored. What is your name?”

“Bao,” Li Hua lied, using her aunt’s name.

“I am called Sihabh. Do you play backgammon, Bao?”

“My grandmother taught me to play when I was a little girl.” Li Hua remembered sitting in the old woman’s garden, listening to the bird song, sipping strong tea, and moving the faded old chips on the ancient board, trying and failing to win. She had been six years old; so long ago.

“Do you remember,” he prompted.

“Yes.”

Sihabh picked up a board from behind his chair, brushed away the sand with his sleeve and placed it on the stand before them. “How about we play a game. If you win, you may go on and take the rock; if you lose, you leave and don’t bother me anymore. Do we have a deal?”

If she lost, Li Hua had no intention of leaving empty handed. They had no guns in the desert but she had no doubt Sihabh would know enough to be afraid of one. She decided however there was no harm in trying the peaceful way first.

“Deal,” she allowed a small smile. Sihabh held out a hand to shake and, pulling back his sleeve, chuckled as Li Hua recoiled in to the back of the chair. His hand was made of metal, jointed, silver fingers built out from, most repulsively of all, a palm with fake lines imprinted upon it. Instinctively, her hand fell to the gun strapped beneath her skirt. “You’re a robot,” she whispered, not bothering to hide her disgust. “No wonder they left you behind.”

“Now, now.” The machine did not seem bothered. “Do you not think robots can play backgammon? Do you not think we get bored every once in a while? Do we have a deal?”

Li Hua was not generally a violent person and considered herself quite gifted at finding alternatives to using her weapons, but in this situation it took all her self-control to keep her hand from grabbing at her gun and instead to shake the hand of the abomination. “Deal,” she murmured once more, loathing the cold feel of the machine against her palm.

The machine opened the board gently and began to arrange the pieces. The board was very old; the triangles were made of cracking mosaic tiles and the columns at the side which held the pieces had lost its cloth lining. The pieces and the dice however were new. The round chips seemed to glow with a deep red or a diamond white; flecks of gold shone from deep within. The dice were cream colored, the dots painted the same black of the machine’s eyes. Li Hua took one in her hands and guessed it was made of bone.

“Red or white,” Sihabh the machine asked as he arranged the pieces.

“Red,” Li Hua decided, and they spun the board around so red would face her.

“Shall we see who goes first?” She nodded and they counted together; one, two, three, and dropped their dice. Li Hua had a five; the machine a three. Li Hua, having the highest number, moved her chips and nodded when she was finished. Sihabh collected the dice in his fist and rolled.

“Do you want to know where the rock came from, Bao?” he asked her.

“Do you know?” he finished his turn and she took the dice for herself, putting more of her pieces between Sihabh the machine’s and the fourth quadrant of the board, a strategy her grandmother had taught her.

“Yes and I will tell you. If you tell me where you are from and who sent you.”

“Easy,” Li Hua smiled to herself and she handed him the dice. “I am from China and I came to this land myself, for a job.”

Sihabh the machine did not seem annoyed like she wanted him to be. “I mean, who told you to fetch the funny little rock.”

“I answered your questions, machine. Now answer mine.”

Sihabh snickered at her; she didn’t think that robots could laugh at all, let alone that sincerely. “It came from the sky.”

“I know that.”

“And I know that you have come from China and that you came here yourself. We have traded our information fairly.”

“But do you know where it came from in the sky,” Li Hua asked as she watched Sihabh’s mechanical hand move the chips. “A planet, a satellite, a star?”

“I might,” Sihabh shrugged as he placed the dice down. “But I will not tell you.”

They played in silence for a few moments, still doing evenly. Li Hua had all of her chips out of the first quadrant and had knocked back one of Sihabh’s as it tried to escape, but he had arranged his pieces so that any move she made would be dangerous, and the quadrant she would find herself stuck in was almost entirely filled with Sihabh’s pieces. It would be nearly impossible to escape. She tossed the dice; a three and a one. No help to her. She stared at the bored, calculating the chances of Sihabh knocking her back into the first quadrant for every place her chip could move. Finally she chose the least likely one; there were only three combinations Sihabh could roll that would trouble her.

“Go on.” Sihabh rolled the dice. It was, of course, for wouldn’t it be far too fair otherwise, one of the three rolls. Li Hua winced but Sihabh hesitated. He might, she realized, not have noticed. Distract him! It was a tactic her grandmother taught her long ago, and an unfair one, but it worked. The only time you can fight bad luck head on, she had joked, distracting Li Hua from a very good move she failed to notice.

“How do you think?” Li Hua said.

Sihabh looked up at her, as puzzled as a machine could be. “What do you mean, Bao?” She was beginning to notice how stiff his movements were, how synthesized his voice, and cursed herself for not realizing what he was before.

“I mean are you conscious? Or are you just programmed for many, many things? Are you going to start saying something foolish like the simple AI’s they had once?”

“Silly like what?”

“I don’t know, but my grandfather always said the old AI’s were always very random. They didn’t make sense most of the time.”

“They improved them. I always make sense, Bao, for I am not a human.”

He turned his attention to the board again. “But are you conscious?” she asked desperately, nearly hysterically.

“I don’t understand?”

“Can you come up with ideas of your own? Can you create? Are you aware? Can you…” she searched for a word, “philosophize?”

“I know nothing else, so I suppose. I have had conversations like this one with you, and I have created what I said. I do not speak from programmed phrases, if that’s what you mean.” He returned to the game and his hand, shining silver in the fiery desert sun, slid his chip three spaces, right on top of hers, scooped up the red chip, and placed it in the middle of the board.

“Back with you,” he murmured jokingly.

“I was trying to distract you,” Li Hua explained impulsively.

“We can think many things at once, Bao,” Sihabh explained. “Because we are very clever.”

“And very smug.”

“No.” His smile was unmoving, his eyes unblinking, his movements chilling. Li Hua considered herself brave, but yet she squirmed. “That is a silly human thing. I am only saying what is true. Your turn.”

Li Hua needed a three to get her chip back in; instead she rolled a one and a five and could not move any piece at all. Sihabh took his turn proudly. Li Hua admittedly knew little about robots. Back home they were rarely used, and when they were their programming was simple, without brains or the ability to think. She had not believed any machine could, and yet here was strange Sihabh, looking oh so real, showing arrogance and pride and amusement. And yet these were twisted in his metal hands, turned into mechanical abominations. Li Hua was appalled that these were things she had ever felt herself now that they were reflected back to her on his plastic face.

“And you. Do you think?” the machine asked her.

“Of course I do.”

“Do you know what I wonder about you and your people. You created us and yet we are better than you. We can do more, think many things at once, and survive just about anything. If we are careful we can live forever. Why would you create something so better than yourself?”

“I didn’t create you,” Li Hua said in disgust. “My people want nothing to do with robots. But you are not better than us. You can’t feel.”

“We are created in your image. Do you not think we resemble you in every way?”

“Look at our hands, Sihabh.” Li Hua was immediately disgusted with herself for using his name.

“A minor defect. Perhaps one day soon your hands will not be so fragile.”

He was winning and she hated it. She despised him more than she despised the desert, the faceless man or woman who had sent her here, more than anything she’d ever hated in her life. She was so full of loathing she was nearly shaking. Her chip was back in the game though, which was good. She picked up the dice and rolled them carefully, slowly, and dropped them gently on to the board. Double fives. With a satisfied grin she moved her piece across the board. Now, they were just about tied.

“I have one more question for you.”

“Than by all means,” Sihabh gestured vaguely with his silver claw, “ask.”

“Do you dream?”

His mechanical smile faltered. “What?”

“What do you want of your…” once more she searched for an appropriate word but finally settled, with careful, hesitant emphasis, “Life.”

“Right now,” he tossed the dice, “I want to win.”

“And then?”

“I want you to walk away, leaving this rock behind. And then I want my friends to return for me.”

“But farther in to the future,” Li Hua explained desperately, “years from now. Where do you want to be?”

“You will laugh.” He hesitated. “But I want to live in one of the cities. I want to have people with me and we will play games. I want to learn chess; I don’t know very many games you see. They taught me backgammon and Chinese checkers but that is it. I quite like games.”

“So you want to be happy,” she summarized cautiously.

“Yes,” he nodded as though he had never thought of it that way. “I do.”

They were so close; he had four pieces remaining on the board, she had two and it was his turn. He rolled the dice carelessly, as if he didn’t notice he was losing. The dice fell; double fours. His smirk gone, he picked up his pieces and placed them on the side of the board. “I win,” he said, a little bit of pride slipping in to his tone.

“I guess I’ll be leaving then,” Li Hua began, taking to her feet and reaching for her gun.

“That easily? No, I’ve changed my mind. I think you and I are going to be friends. You see, I don’t think my friends are coming back. You want your rock; I don’t want to be left here to rot. So we will travel this desert together and then I will give you your rock.”

“I don’t think so.” Li Hua had forgotten how much she loved this part, the little bit of fear that flashed in their eyes, how easily they submitted. “Because what is to stop me from shooting you.” She aimed her gun at his face.

Sihabh was unaffected. “Yourself, Bao. You will not shoot me. You find me puzzling or, dare I say it, intriguing.”

“You think I am weak.”

“I think you are human.”

Li Hua met his eyes for a very long time. Neither of them blinked. The sun shone on. Finally, she returned the gun to its holster. “All right,” she said numbly. “Let’s go.”

Sihabh took the rock and Li Hua took the knapsack. They left the stand and the backgammon board where it was, to one day fall apart and be buried by the sand, claimed by the desert. And they walked, Li Hua adjusting the veil to conceal her face and Sihabh hiding his mechanical hand in his sleeve for it shone too brightly in the sun.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.